On March 2, a disturbing report hit the desks of U.S. counterintelligence officials in Washington. For months, American spy hunters had scrambled to uncover details of Russia’s influence operation against the 2016 presidential election. In offices in both D.C. and suburban Virginia, they had created massive wall charts to track the different players in Russia’s multipronged scheme. But the report in early March was something new.

It described how Russia had already moved on from the rudimentary email hacks against politicians it had used in 2016. Now the Russians were running a more sophisticated hack on Twitter. The report said the Russians had sent expertly tailored messages carrying malware to more than 10,000 Twitter users in the Defense Department. Depending on the interests of the targets, the messages offered links to stories on recent sporting events or the Oscars, which had taken place the previous weekend. When clicked, the links took users to a Russian-controlled server that downloaded a program allowing Moscow’s hackers to take control of the victim’s phone or computer–and Twitter account.

As they scrambled to contain the damage from the hack and regain control of any compromised devices, the spy hunters realized they faced a new kind of threat. In 2016, Russia had used thousands of covert human agents and robot computer programs to spread disinformation referencing the stolen campaign emails of Hillary Clinton, amplifying their effect. Now counterintelligence officials wondered: What chaos could Moscow unleash with thousands of Twitter handles that spoke in real time with the authority of the armed forces of the United States? At any given moment, perhaps during a natural disaster or a terrorist attack, Pentagon Twitter accounts might send out false information. As each tweet corroborated another, and covert Russian agents amplified the messages even further afield, the result could be panic and confusion.

For many Americans, Russian hacking remains a story about the 2016 election. But there is another story taking shape. Marrying a hundred years of expertise in influence operations to the new world of social media, Russia may finally have gained the ability it long sought but never fully achieved in the Cold War: to alter the course of events in the U.S. by manipulating public opinion. The vast openness and anonymity of social media has cleared a dangerous new route for antidemocratic forces. “Using these technologies, it is possible to undermine democratic government, and it’s becoming easier every day,” says Rand Waltzman of the Rand Corp., who ran a major Pentagon research program to understand the propaganda threats posed by social media technology.

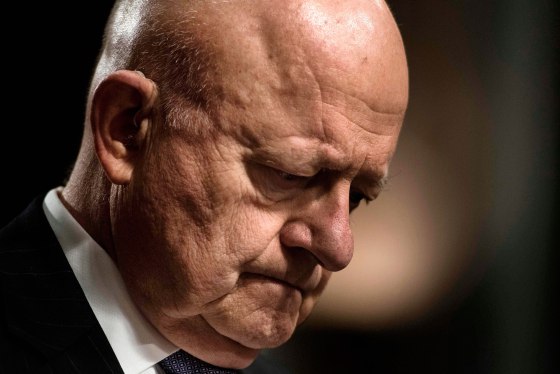

Current and former officials at the FBI, at the CIA and in Congress now believe the 2016 Russian operation was just the most visible battle in an ongoing information war against global democracy. And they’ve become more vocal about their concern. “If there has ever been a clarion call for vigilance and action against a threat to the very foundation of our democratic political system, this episode is it,” former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper testified before Congress on May 8.

If that sounds alarming, it helps to understand the battlescape of this new information war. As they tweet and like and upvote their way through social media, Americans generate a vast trove of data on what they think and how they respond to ideas and arguments–literally thousands of expressions of belief every second on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit and Google. All of those digitized convictions are collected and stored, and much of that data is available commercially to anyone with sufficient computing power to take advantage of it.

That’s where the algorithms come in. American researchers have found they can use mathematical formulas to segment huge populations into thousands of subgroups according to defining characteristics like religion and political beliefs or taste in TV shows and music. Other algorithms can determine those groups’ hot-button issues and identify “followers” among them, pinpointing those most susceptible to suggestion. Propagandists can then manually craft messages to influence them, deploying covert provocateurs, either humans or automated computer programs known as bots, in hopes of altering their behavior.

That is what Moscow is doing, more than a dozen senior intelligence officials and others investigating Russia’s influence operations tell TIME. The Russians “target you and see what you like, what you click on, and see if you’re sympathetic or not sympathetic,” says a senior intelligence official. Whether and how much they have actually been able to change Americans’ behavior is hard to say. But as they have investigated the Russian 2016 operation, intelligence and other officials have found that Moscow has developed sophisticated tactics.

In one case last year, senior intelligence officials tell TIME, a Russian soldier based in Ukraine successfully infiltrated a U.S. social media group by pretending to be a 42-year-old American housewife and weighing in on political debates with specially tailored messages. In another case, officials say, Russia created a fake Facebook account to spread stories on political issues like refugee resettlement to targeted reporters they believed were susceptible to influence.

As Russia expands its cyberpropaganda efforts, the U.S. and its allies are only just beginning to figure out how to fight back. One problem: the fear of Russian influence operations can be more damaging than the operations themselves. Eager to appear more powerful than they are, the Russians would consider it a success if you questioned the truth of your news sources, knowing that Moscow might be lurking in your Facebook or Twitter feed. But figuring out if they are is hard. Uncovering “signals that indicate a particular handle is a state-sponsored account is really, really difficult,” says Jared Cohen, CEO of Jigsaw, a subsidiary of Google’s parent company, Alphabet, which tackles global security challenges.

Like many a good spy tale, the story of how the U.S. learned its democracy could be hacked started with loose lips. In May 2016, a Russian military intelligence officer bragged to a colleague that his organization, known as the GRU, was getting ready to pay Clinton back for what President Vladimir Putin believed was an influence operation she had run against him five years earlier as Secretary of State. The GRU, he said, was going to cause chaos in the upcoming U.S. election.

What the officer didn’t know, senior intelligence officials tell TIME, was that U.S. spies were listening. They wrote up the conversation and sent it back to analysts at headquarters, who turned it from raw intelligence into an official report and circulated it. But if the officer’s boast seems like a red flag now, at the time U.S. officials didn’t know what to make of it. “We didn’t really understand the context of it until much later,” says the senior intelligence official. Investigators now realize that the officer’s boast was the first indication U.S. spies had from their sources that Russia wasn’t just hacking email accounts to collect intelligence but was also considering interfering in the vote. Like much of America, many in the U.S. government hadn’t imagined the kind of influence operation that Russia was preparing to unleash on the 2016 election. Fewer still realized it had been five years in the making.

In 2011, protests in more than 70 cities across Russia had threatened Putin’s control of the Kremlin. The uprising was organized on social media by a popular blogger named Alexei Navalny, who used his blog as well as Twitter and Facebook to get crowds in the streets. Putin’s forces broke out their own social media technique to strike back. When bloggers tried to organize nationwide protests on Twitter using #Triumfalnaya, pro-Kremlin botnets bombarded the hashtag with anti-protester messages and nonsense tweets, making it impossible for Putin’s opponents to coalesce.

Putin publicly accused then Secretary of State Clinton of running a massive influence operation against his country, saying she had sent “a signal” to protesters and that the State Department had actively worked to fuel the protests. The State Department said it had just funded pro-democracy organizations. Former officials say any such operations–in Russia or elsewhere–would require a special intelligence finding by the President and that Barack Obama was not likely to have issued one.

After his re-election the following year, Putin dispatched his newly installed head of military intelligence, Igor Sergun, to begin repurposing cyberweapons previously used for psychological operations in war zones for use in electioneering. Russian intelligence agencies funded “troll farms,” botnet spamming operations and fake news outlets as part of an expanding focus on psychological operations in cyberspace.

It turns out Putin had outside help. One particularly talented Russian programmer who had worked with social media researchers in the U.S. for 10 years had returned to Moscow and brought with him a trove of algorithms that could be used in influence operations. He was promptly hired by those working for Russian intelligence services, senior intelligence officials tell TIME. “The engineer who built them the algorithms is U.S.-trained,” says the senior intelligence official.

Soon, Putin was aiming his new weapons at the U.S. Following Moscow’s April 2014 invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. considered sanctions that would block the export of drilling and fracking technologies to Russia, putting out of reach some $8.2 trillion in oil reserves that could not be tapped without U.S. technology. As they watched Moscow’s intelligence operations in the U.S., American spy hunters saw Russian agents applying their new social media tactics on key aides to members of Congress. Moscow’s agents broadcast material on social media and watched how targets responded in an attempt to find those who might support their cause, the senior intelligence official tells TIME. “The Russians started using it on the Hill with staffers,” the official says, “to see who is more susceptible to continue this program [and] to see who would be more favorable to what they want to do.”

On Aug. 7, 2016, the infamous pharmaceutical executive Martin Shkreli declared that Hillary Clinton had Parkinson’s. That story went viral in late August, then took on a life of its own after Clinton fainted from pneumonia and dehydration at a Sept. 11 event in New York City. Elsewhere people invented stories saying Pope Francis had endorsed Trump and Clinton had murdered a DNC staffer. Just before Election Day, a story took off alleging that Clinton and her aides ran a pedophile ring in the basement of a D.C. pizza parlor.

Congressional investigators are looking at how Russia helped stories like these spread to specific audiences. Counterintelligence officials, meanwhile, have picked up evidence that Russia tried to target particular influencers during the election season who they reasoned would help spread the damaging stories. These officials have seen evidence of Russia using its algorithmic techniques to target the social media accounts of particular reporters, senior intelligence officials tell TIME. “It’s not necessarily the journal or the newspaper or the TV show,” says the senior intelligence official. “It’s the specific reporter that they find who might be a little bit slanted toward believing things, and they’ll hit him” with a flood of fake news stories.

Russia plays in every social media space. The intelligence officials have found that Moscow’s agents bought ads on Facebook to target specific populations with propaganda. “They buy the ads, where it says sponsored by–they do that just as much as anybody else does,” says the senior intelligence official. (A Facebook official says the company has no evidence of that occurring.) The ranking Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee, Mark Warner of Virginia, has said he is looking into why, for example, four of the top five Google search results the day the U.S. released a report on the 2016 operation were links to Russia’s TV propaganda arm, RT. (Google says it saw no meddling in this case.) Researchers at the University of Southern California, meanwhile, found that nearly 20% of political tweets in 2016 between Sept. 16 and Oct. 21 were generated by bots of unknown origin; investigators are trying to figure out how many were Russian.

As they dig into the viralizing of such stories, congressional investigations are probing not just Russia’s role but whether Moscow had help from the Trump campaign. Sources familiar with the investigations say they are probing two Trump-linked organizations: Cambridge Analytica, a data-analytics company hired by the campaign that is partly owned by deep-pocketed Trump backer Robert Mercer; and Breitbart News, the right-wing website formerly run by Trump’s top political adviser Stephen Bannon.

The congressional investigators are looking at ties between those companies and right-wing web personalities based in Eastern Europe who the U.S. believes are Russian fronts, a source familiar with the investigations tells TIME. “Nobody can prove it yet,” the source says. In March, McClatchy newspapers reported that FBI counterintelligence investigators were probing whether far-right sites like Breitbart News and Infowars had coordinated with Russian botnets to blitz social media with anti-Clinton stories, mixing fact and fiction when Trump was doing poorly in the campaign.

There are plenty of people who are skeptical of such a conspiracy, if one existed. Cambridge Analytica touts its ability to use algorithms to microtarget voters, but veteran political operatives have found them ineffective political influencers. Ted Cruz first used their methods during the primary, and his staff ended up concluding they had wasted their money. Mercer, Bannon, Breitbart News and the White House did not answer questions about the congressional probes. A spokesperson for Cambridge Analytica says the company has no ties to Russia or individuals acting as fronts for Moscow and that it is unaware of the probe.

Democratic operatives searching for explanations for Clinton’s loss after the election investigated social media trends in the three states that tipped the vote for Trump: Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. In each they found what they believe is evidence that key swing voters were being drawn to fake news stories and anti-Clinton stories online. Google searches for the fake pedophilia story circulating under the hashtag #pizzagate, for example, were disproportionately higher in swing districts and not in districts likely to vote for Trump.

The Democratic operatives created a package of background materials on what they had found, suggesting the search behavior might indicate that someone had successfully altered the behavior in key voting districts in key states. They circulated it to fellow party members who are up for a vote in 2018.

Even as investigators try to piece together what happened in 2016, they are worrying about what comes next. Russia claims to be able to alter events using cyberpropaganda and is doing what it can to tout its power. In February 2016, a Putin adviser named Andrey Krutskikh compared Russia’s information-warfare strategies to the Soviet Union’s obtaining a nuclear weapon in the 1940s, David Ignatius of the Washington Post reported. “We are at the verge of having something in the information arena which will allow us to talk to the Americans as equals,” Krutskikh said.

But if Russia is clearly moving forward, it’s less clear how active the U.S. has been. Documents released by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden and published by the Intercept suggested that the British were pursuing social media propaganda and had shared their tactics with the U.S. Chris Inglis, the former No. 2 at the National Security Agency, says the U.S. has not pursued this capability. “The Russians are 10 years ahead of us in being willing to make use of” social media to influence public opinion, he says.

There are signs that the U.S. may be playing in this field, however. From 2010 to 2012, the U.S. Agency for International Development established and ran a “Cuban Twitter” network designed to undermine communist control on the island. At the same time, according to the Associated Press, which discovered the program, the U.S. government hired a contractor to profile Cuban cell phone users, categorizing them as “pro-revolution,” “apolitical” or “antirevolutionary.”

Much of what is publicly known about the mechanics and techniques of social media propaganda comes from a program at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) that the Rand researcher, Waltzman, ran to study how propagandists might manipulate social media in the future. In the Cold War, operatives might distribute disinformation-laden newspapers to targeted political groups or insinuate an agent provocateur into a group of influential intellectuals. By harnessing computing power to segment and target literally millions of people in real time online, Waltzman concluded, you could potentially change behavior “on the scale of democratic governments.”

In the U.S., public scrutiny of such programs is usually enough to shut them down. In 2014, news articles appeared about the DARPA program and the “Cuban Twitter” project. It was only a year after Snowden had revealed widespread monitoring programs by the government. The DARPA program, already under a cloud, was allowed to expire quietly when its funding ran out in 2015.

In the wake of Russia’s 2016 election hack, the question is how to research social media propaganda without violating civil liberties. The need is all the more urgent because the technology continues to advance. While today humans are still required to tailor and distribute messages to specially targeted “susceptibles,” in the future crafting and transmitting emotionally powerful messages will be automated.

The U.S. government is constrained in what kind of research it can fund by various laws protecting citizens from domestic propaganda, government electioneering and intrusions on their privacy. Waltzman has started a group called Information Professionals Association with several former information operations officers from the U.S. military to develop defenses against social media influence operations.

Social media companies are beginning to realize that they need to take action. Facebook issued a report in April 2017 acknowledging that much disinformation had been spread on its pages and saying it had expanded its security. Google says it has seen no evidence of Russian manipulation of its search results but has updated its algorithms just in case. Twitter claims it has diminished cyberpropaganda by tweaking its algorithms to block cleverly designed bots. “Our algorithms currently work to detect when Twitter accounts are attempting to manipulate Twitter’s Trends through inorganic activity, and then automatically adjust,” the company said in a statement.

In the meantime, America’s best option to protect upcoming votes may be to make it harder for Russia and other bad actors to hide their election-related information operations. When it comes to defeating Russian influence operations, the answer is “transparency, transparency, transparency,” says Rhode Island Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse. He has written legislation that would curb the massive, anonymous campaign contributions known as dark money and the widespread use of shell corporations that he says make Russian cyberpropaganda harder to trace and expose.

But much damage has already been done. “The ultimate impact of [the 2016 Russian operation] is we’re never going to look at another election without wondering, you know, Is this happening, can we see it happening?” says Jigsaw’s Jared Cohen. By raising doubts about the validity of the 2016 vote and the vulnerability of future elections, Russia has achieved its most important objective: undermining the credibility of American democracy.

For now, investigators have added the names of specific trolls and botnets to their wall charts in the offices of intelligence and law-enforcement agencies. They say the best way to compete with the Russian model is by having a better message. “It requires critical thinkers and people who have a more powerful vision” than the cynical Russian view, says former NSA deputy Inglis. And what message is powerful enough to take on the firehose of falsehoods that Russia is deploying in targeted, effective ways across a range of new media? One good place to start: telling the truth.

–With reporting by PRATHEEK REBALA/WASHINGTON

Correction: The original version of this story misstated Jared Cohen’s title. He is CEO, not president.

Massimo Calabresi